Beyond OWS: Problem #2: The Problem with Politics

This is part two of my series on Beyond Occupy Wall Street. You can find part one, where I put the boot into contemporary economic dogma here.

In this post, I focus on politics. Or, more specifically, on the failure of the 20th century political paradigm to accord with a 21st century world. Basically, the Left-Right political spectrum as we know it is defunct and, as a result, we’re seeing the political parties of the last century struggle in many democracies around the world, not least in Anglophone world.

In the U.S., Obama was supposed to liberate the country from the bitter partisan politics of the Bush Jr. era, where the Left and the Right had become violently polarised and infected by base-appeasing populism, meanwhile lacking the courage to make the tough decisions that are required to set the country straight. But even Obama – with his feel-good “there’s only the United States of America” – failed to bring the warring parties together.

The recent debt crisis is but one of many, many examples of the abject failure of the two major U.S. parties to put their knives down and govern in the interests of the nation. Not to mention the banality of Fox News and the Tea Party, offering hopelessly simplistic solutions to complex problems – some real, and some fictitious.

In the U.K. and Australia the last elections resulted in hung parliaments, largely due to disillusionment with the major parties and the parlous calibre of political debate. Both countries saw a protest vote lobbed against a long-term sitting government that had gone stale, yet the voters proved unenthused at the prospect of the alternative governments on offer. The result is minority government, with uneasy coalitions formed, which are unlikely to survive the next election.

Left, Right, Wrong

But these are only symptoms of a deeper malaise. The political spectrum as it was defined in the 20th century is no longer relevant. The 20th century notions of Left and Right are now defunct.

The Old Left was characterised by two main values: economic egalitarianism; and social progressivism. The former often manifest in terms of socialist economic policies, stressing central planning, government regulation, wealth redistribution, welfare and being highly mistrustful of the profit-seeking free market. The latter manifest in terms of erosion of state interference in individual behaviour, instead encouraging individual expression, and government non-involvement in moral issues.

The Old Left was characterised by two main values: economic egalitarianism; and social progressivism. The former often manifest in terms of socialist economic policies, stressing central planning, government regulation, wealth redistribution, welfare and being highly mistrustful of the profit-seeking free market. The latter manifest in terms of erosion of state interference in individual behaviour, instead encouraging individual expression, and government non-involvement in moral issues.

The Old Right was characterised by two main values in opposition to the Old Left: economic meritocracy; and social conservatism. The former manifest in promoting market economics (although the Old Right still believed in regulation, mainly protecting the current captains of industry – and in some ways nothing has changed…). The latter manifest in terms of social conformity, resistance to social change and discomfort with rampant individual expression.

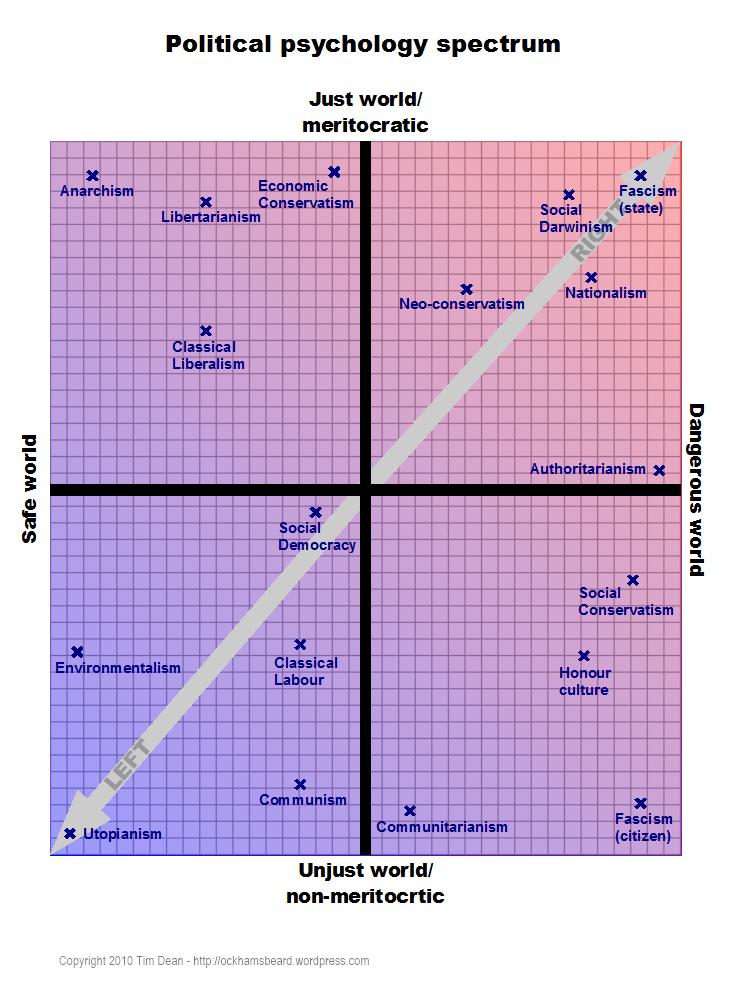

To understand this political dichotomy, it helps to understand the worldview of each side – which is something I explain in these two posts in more detail – but here’s the tl;dr:

The Old Right saw the world as being a generally dangerous, dog eat dog world, where to survive and flourish one needs to be strong and disciplined, and loyal to one’s group. The world is a meritocracy, such that if you work hard, you’ll succeed, and if you coddle people then they’ll only be worse off. In this worldview, people are generally nasty and need to be tamed – either through self-discipline, by conforming to a group moral code, or through punishment.

The Old Left saw the world as generally a safe place and people as generally good, so if you leave them to their own devices, they’ll naturally be nice and will get along with each other. However, it rejected the idea that one’s success is entirely down to their own efforts. The Old Left saw the each of us as being reliant on the broader community in order to find success. It saw failure as being an environmental or conditioning issue, thus an emphasis on rehabilitation rather than punishment.

The problem is, people born after the 1960s don’t necessarily see the world in these ways anymore. Instead, I would suggest that most people under 40 tend to see the world as a hybrid of the two: the world is relatively safe, and people generally good; but it’s a meritocracy where if you work hard you’ll likely succeed. Which makes sense, really, if you’ve grown up in a Western democracy in the late-20th Century.

The upshot is, neither the Left or the Right have the values that mesh with how most people feel these days – particularly young people. A growing number of people wish for a party that is economically liberal – that believes in a carefully regulated market rather than central planning or organised labour and unions – and also advocates social progressivism – allowing people to live how they want.

Yet the Right has become invaded in the U.S. by neoliberalists, who go too far in terms of economic liberalism, and religious fundamentalists, who go too far in terms of social conservatism. In the U.K. and Australia, the Right parties are softer economically, but have become the natural home of social conservatives, thus scare off more progressively-minded young people.

The Left is typically wedded to the unions and labour movements, and when it moves to the Right in economics, it ends up losing its distinctiveness. In Australia, the Labor party is torn between inner city educated social progressives and suburban middle-class workers. The former want things like a gay marriage and a compassionate policy on asylum seekers, and the latter have left the unions in droves and want a greater focus on economic growth. Labor’s policies almost perfectly alienate both sides equally well.

New Corruption

Meanwhile, all three countries – and many others besides – are seeing good governance undermined by big business, lobby groups and special interests. These three represent the new corruption of politics today. It’s these forces that seek to shape the political and economic landscape to their benefit even if it comes at a cost to everyone else.

In the U.S. there is the pharmaceutical lobby, the energy companies, Wall Street, the richly-funded think tanks and the entire political lobbyist industry that is strangling Washington D.C.. In the U.K. the recent phone tapping scandal revealed the extent to which the politicians were in the pockets of Murdoch’s press.

In Australia, the big mining companies used a $22 million advertising campaign to fool the public into thinking a proposed mining tax would cripple the country, the success of which has led to climate denialists and gambling proponents trying the same caper in their own areas.

The thing is, in any social or economic landscape, there are winners and losers. But that particular landscape might not be the most efficient or most just. Changing to a new landscape might mean that everyone – or at least a greater number of people – are better off. However, it usually means some existing winners become losers.

It’s the job of special interests to prevent the shift from one social or economic landscape to another if the vested interests they serve will cease being winners. And they can do this because the current winners are the ones with the power and resources to prevent change, while the future winners lack this power.

So, basically, the upshot is: politics has failed us. It’s divisive, it’s ideologically out of step with a growing proportion of the population, and it’s been corrupted by special interests.

I want to stress that democracy itself hasn’t necessarily failed. By criticising politics the way I’m doing now, I’m employing the democratic system in an appeal for change. My criticisms – and, I believe, those of the Occupy Wall Street movement – should be targeted at bad ideologies and individuals within the democratic system, but we should work to shore up the system itself – and use it for change.

In the next in my Occupy Wall Street series I’ll tackle Problem #3: society, talking about what society is for – and what it should be for – about the failure of reason and Enlightenment values, and about the collapse of community and the rise of individualism. After that, some prescriptive suggestions. Stay tuned.

10 Comments

Ben · 1st November 2011 at 10:59 pm

What seems to happen, at least in the US and probably elsewhere, is that politicians appeal first to the values of their base – a relatively small group of people whose overall ideological makeup varies little. Once they have secured the trust of their base they appeal more broadly to everyone else in the community (of course, they must if they hope to win an election). But to get to a stage where they are even able to appeal to a wider set of values they must (to the best of their ability) coddle the base. They must pass the ‘purity test’ – that is, that must demonstrate their allegiance to the values of the Old Left or the Old Right. Any sign of heterogeneity or the ‘Third Way’ and they are cast aside as not being ‘true’ conservatives/liberals; not being pure enough. So long as this process continues our thinking about politics will be framed in the terms of the Old Left and the Old Right. It has become a tradition that neither side seems serious about moving away from.

GTChristie · 2nd November 2011 at 2:37 am

Both posts so far are good; the second even better than the first. I won’t comment now. I’m just stopping in to let you know I’m reading and I think you’re on the right track.

Tim Dean · 2nd November 2011 at 8:37 am

Hi Ben. I think what you’re characterising there is far more a U.S. phenomenon, given the idiosyncrasies of the primary system. U.S. politicians – particularly presidential candidates – are forced to make a popular appeal to their base before a popular appeal to the entire nation.

In the U.K. and Australia, candidates are pre-selected by their party. This still means they must appeal to their party, but the party machine is (often) more concerned about general electability than the public bases.

But the problem you mention still exists, in that politicians from either party are products of that party. It’s difficult for a Third Way to emerge from the existing parties, which is why in a later post I will suggest a new political movement ought to emerge, with its own parties and candidates.

JW Gray · 2nd November 2011 at 10:01 am

The “old liberal” ideology you describe doesn’t really exist in the USA. Both parties are very conservative, pro-capitalism, etc.

What makes you think this is a “new” form of corruption? Those in power have continually fought for advantages throughout history.

GTChristie · 6th November 2011 at 11:12 pm

Corruption isn’t new, but many of its specific forms are. Big business, for example, consists of multinational corporations with annual budgets larger than the GDP of many sovereign nations, operating in (and influencing) a global economy the scale of which has no historical precedent. Power in the hands of a few isn’t new, but the extent or reach of that power is deeper and more ubiquitous than ever. So I don’t think it’s a fallacy to point out that the opportunities and practical means of corruption are deeper and more insidious now. Yes, those in power have continually fought for advantages throughout history. In fact, such advantages are not, ipso facto, corrupt (corruption being an abuse or misuse of power). But today those advantages, if attained and abused, enable an historically unprecedented intensity and extent of harm to ordinary people.

Tim Dean · 6th November 2011 at 11:25 pm

I should add that, indeed, such special interests have existed for a long time. But ‘corruption’ these days is typically defined in terms of graft and nepotism. But these forms of corruption have been greatly reduced in Western nations (one of the unsung triumphs of liberalism, IMO). That’s why I call influence by money and special interests on political decision makers to be the ‘new’ corruption, and one that we need to focus on and eradicate with great urgency.

Tincup · 8th November 2011 at 4:38 am

Nice overview. I would say that our government…focusing on the United states…in reality…has two additional branches of government not originally intended…the Press…and the Lobby Firms…

On a personal note…I can’t identify with the left or the right just as you pointed out in your estimate of what is going on with younger generations…although I am not that young…fall into Generation X.

I think one principal we must come to realize is…man/woman is not created equal at birth…some human beings are simply more intelligent, more talented…at birth…and they should be nurtured to reach their potential by the systems at large…but….those of us not as gifted…must also be nurtured and developed to the best of our ability…there is enough work…enough resources…enough everything for us to move forward…but we as individuals, towns, cities, states, countries, as a species…need to make many sacrafices and changes to turn this mess around…our current government and economic structures and educational institutions and visonless goals aint going to get her done:)

Page not found « Ockham's Beard · 20th November 2011 at 3:21 pm

[…] Beyond OWS: Problem #2: The Problem with Politics […]

Beyond OWS: Where to Next? « Ockham's Beard · 20th November 2011 at 3:23 pm

[…] that have inspired the Occupy Wall Street movement – problems with our current economics, politics and society – even if the Occupy movement itself is yet to identify these problems itself […]

Beyond OWS: The Slow Revolution « Ockham's Beard · 20th November 2011 at 3:26 pm

[…] that have inspired the Occupy Wall Street movement – problems with our current economics, politics and society – even if the Occupy movement itself is yet to identify these problems itself […]